Written By: Kyle Niblett

Interview By: Ana C. Forrister

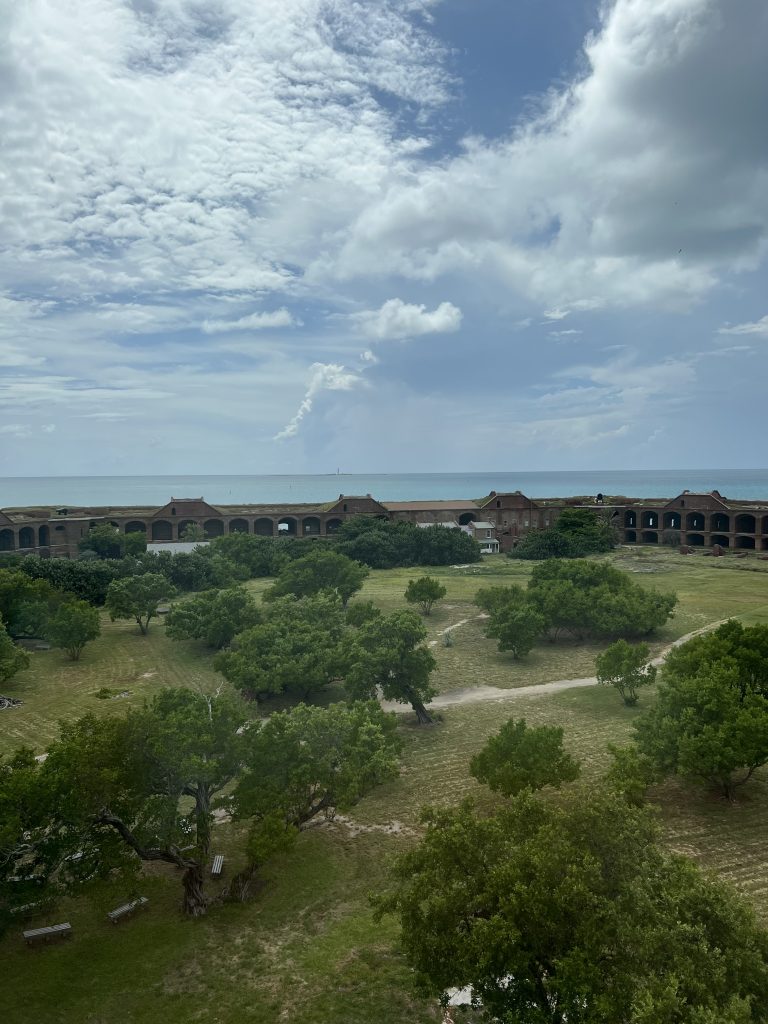

Nearly 70 miles west of Key West, the largest all-masonry fort in the United States rises from the land of sunken pirate ships surrounded by picturesque blue waters, superlative coral reefs and marine life spied on by an assortment of exotic birds. Designated as a National Monument by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935 and later re-designated as Dry Tortugas National Park in 1992 by Congress, this worldwide attraction has needed some tender, loving care since its inception in the mid-1800s.

That is why the National Park Service (NPS) has signed Chuck Baxter (BDES ’86, MARCH ’88) and his firm CROFT & Associates to an IDIQ (indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity) contract. As a senior associate at CROFT, the Kennesaw, Georgia native is tasked with renovating and restoring the historic buildings and structures on the islands. With these projects originally being constructed from the 1850s to the 1920s, his work helps to further NPS’ mission of preserving the natural and cultural resources of its National Parks for future generations.

“Your grandfather or my grandfather could have gone to a National Park 60, 70, or even 80 years ago when they were a kid, and the view they saw then is the same view that we can see now,” said Baxter when asked why he enjoys his work on the island. “Everything else in the world changes, but you can visit a National Park and see it almost the way it was when your grandparents visited. I think that is where my personal fulfillment comes from when working on these historic sites.”

The biggest project assigned to Baxter by the NPS as a project manager at Dry Tortugas is the second lighthouse keeper’s quarters at Loggerhead Key, which is three miles further west than Fort Jefferson. With the quarters being built in the 1920s and a kitchen building being constructed in the 1850s for the original keeper’s house, he must work diligently on the renovation and restoration of both, so biologists can spend the night there and study sea turtles and other marine life.

Other projects include restoring a NPS dock at Loggerhead Key that has eroded over time due to the strong west current moving sand across the island, as well as a wastewater treatment facility for the near dozen people who work at Fort Jefferson. The latter of which is mostly just restoration, such as upgrading to hurricane-proof windows without losing the look of the historic windows.

“Honestly, it’s fun to go visit the places,” Baxter said. “Getting back to my roots in historic preservation is great because now I get to do it every day.”

Baxter earned his first degree from UF in 1986 with a bachelor’s degree in architecture. In 1988, he left Gainesville with his Master of Architecture with a specialization in architectural preservation. That degree is now known in the College of Design, Construction and Planning as a master’s degree in historic preservation.

“The preservation background that I developed in graduate school helped me throughout the years with the few historic preservation projects I was able to work on,” Baxter said. “I think a lot of the time you think about, even before you graduate, how you wish you could go back to school at the University of Florida.”

When he is not preserving historic structures, it’s the relationships he built at UF, with people he spent hours in studios with, that he works hard to maintain.

“My group from graduate school still gets together regularly every few years,” Baxter finished with. “It is a lot of fun.”

Since leaving the Sunshine State, he has worked on various projects, including the restoration of the Reading Terminal and Trainshed in Philadelphia, which was completed in 1893 as the largest single-span arched-roof train shed in the world. Other historic structures Baxter has worked on include Cape Lookout National Seashore, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Shenandoah National Park, Virgin Islands National Park and even a 400-year-old fort in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

“One of the coolest things in my life is using materials and practices from days gone by on historic structures to make sure history is protected as opposed to destroyed,” Baxter said.