By: Mia Alfonsi

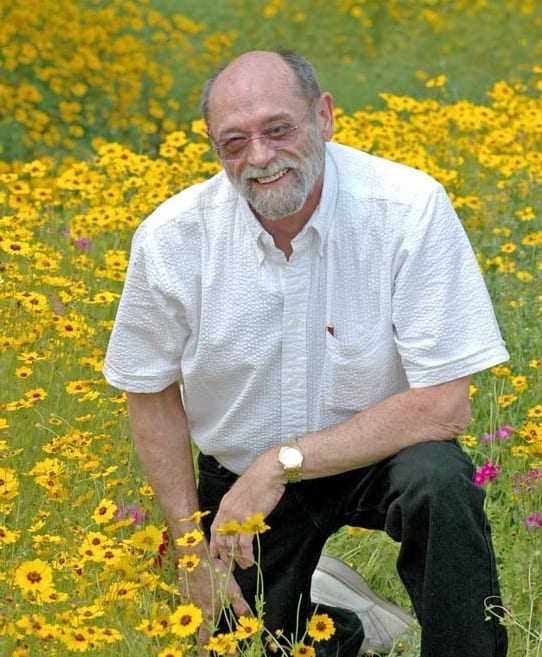

Dotted along Florida’s seemingly eternal stretches of roads and trails are spontaneous patches of vibrant life – native wildflowers, including Florida’s state wildflower, Coreopsis. Fiery reds, deep oranges, sultry blues and happy yellows greet drivers on either side, showcasing their subtle beauty. These plants are crucial actors in ecosystems, sustaining life for various species of birds and butterflies, and their prominent presence across the state can be associated with the decades of work and lifelong pursuit of Gary Henry, a 1971 UF landscape architecture graduate.

Henry’s legacy still lives on throughout Florida today, most notably through sales of the Florida Wildflower License Plate and the Florida Wildflower Foundation (FWF), an organization he helped establish to support research, education and planting of Coreopsis. Authorized by the Florida Legislature in 1999, the plates have raised over $4.25 million for wildflower research.

Obtaining mixed results from his experimentation with roadside wildflowers while working with the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT), Gary knew the organization needed to do research.

“The license plate and the Foundation actually became the vehicle to fund research on native wildflowers,” says FWF’s current Executive Director Lisa Roberts.

The Foundation’s most successful program works to create pollinator corridors along the highways, trails systems and through natural areas and urban centers. These corridors support the vital symbiotic relationships between plants and insects, according to Roberts.

Jeff Caster, Henry’s friend of 30 years, former co-worker and mentee, proclaims that Henry’s interest in his work at the FDOT was sparked and enhanced by his experience working at a nursery in high school, but further compounded by his landscape architecture degree and the value that he saw in Florida’s native wildflowers, both aesthetically and ecologically. Henry retired from FDOT in 2001, but Caster remained until 2020 and carried on with Florida’s roadside design and management.

“Gary would say [creating the foundation] is the most influential thing he did.” Caster said. “He created this vast body of scientific knowledge that didn’t exist. The popularity of wildflowers and wildflower conservation in Florida has really sky-rocketed because of him.”

Henry championed a novel, but timeless, program and was able to rally support for his vision, forming a coalition of individuals mostly from the Florida Federation of Garden Clubs (FFGC) and prominent figures in society including former Lieutenant Governor Buddy MacKay and his wife, former First Lady Anne MacKay.

“I was in and out of the capitol building, and I ran into Gary,” Anne MacKay said. “He was lobbying and trying to gain some traction with the Garden Clubs to push the State Wildflower License Plate program forward.”

MacKay was drawn to Henry’s project not only for his “gentle, patient soul” and “knowledgeable” repertoire but also for her interest in state-wide initiatives that focused on preserving the environment. The MacKays helped Henry obtain signatures for his program petition and pass the initiative through legislation in 1999.

“We were just in the right place at the right time, and Gary being at FDOT, was the right person,” MacKay said. “He was a faithful pursuer of this project.”

Henry’s hearty list of initiatives, achievements and awards such as the FFGC Medal for Achievement in Horticulture and the FWF’s Friend of Florida’s Wildflowers Award, now called the Coreopsis Award, is cemented by his considerateness, both toward his projects and the people in his life.

“He was one of the first landscape architects that I met and to some extent, inspired me to become a landscape architect,” Caster said.

Caster met Henry in the 80s at a voluntary meeting for Arbor Green, a grassroots Tallahassee-based non-profit that planted trees along highways. But their relationship came full circle when Caster accepted a job at the FDOT in 1994 after earning his master’s degree at Cornell University.

“It was almost like it was meant to be,” Caster says, reminiscing on the memory. “I interviewed with him and his supervisor, and I got the job. I got to be mentored by him for seven years.”

While working together at FDOT, Henry and Caster travelled across Florida to Department offices, advocating for their ideas and trying to mobilize support. Caster took notice of how Henry was received by those he encountered.

“Everywhere he went he was greeted cheerfully; people were genuinely happy to see Gary,” Caster said.

But Henry’s revered reputation was not just acknowledged professionally. Whether it was a recommendation for a contractor, a new dentist or barber in Tallahassee or offering a teaching moment, Henry was always looking out for those close to him. Caster says his whole family was on the receiving end of Henry’s kindness.

“It was after he retired that we became close friends,” Caster said genuinely. “We grew to be best friends over the past fifteen years, and I miss him very much. He’d been to every holiday and special gathering at my home. He just became part of my family.”

For the expanse of his career, Henry championed programs that were ahead of his time, according to Caster. He started at FDOT before there had ever been an Earth Day and coming into the department with a landscape architecture degree, Henry was outnumbered by established engineers. The things he was advocating for then, today are mainstream.

Henry went to school in the 60s and 70s when schools were still segregated and new roads were created by being cleared and bulldozed through, with little regard for how this would affect the surrounding ecosystems.

During this era, wildflowers were symbolic of a strong division in the U.S., both politically and socially, and the global “Flower power” movement. The ever-conservative thinking of FDOT often acted as another obstacle for Henry, Caster states.

“He got a lot of push back, but he wasn’t deterred,” Caster said. “Gary was satisfied with small victories.”

Perhaps most telling of Henry’s humble nature was that he let his work speak for himself. He was always “happy sitting in the back row,” putting faith into the hands of those he trusted to continue his legacy.

“For 50 years, Gary stood up for wild Florida,” Caster said. “If he had never done that, maybe Florida would be years behind. But, there are many amazing landscape architects who continue doing this work everywhere.”

Sharing this sentiment, Lisa Roberts, the current executive director of the FWF, says she will forever cherish her and Henry’s phone calls; she, too, was greatly impacted by Henry’s congeniality and willingness to lend a helping hand.

“Gary was just always there for me,” Roberts said, recalling her first phone call with Henry after she received the position. “He gave me an hour of his time, and he didn’t even know me. He wanted to help people learn what they needed to learn to be successful.”

Roberts believes that without Henry, there would be no FWF today.

“Gary was fully committed to the success of our organization, even until the end,” Roberts said. “He gave his time selflessly, and he was the one person I knew that would come through on anything I asked him.”

In recognition of Henry’s contributions to Florida and its native species, the FWF’s board of directors established the Gary Henry Endowment for the study of Florida’s native wildflowers in UF’s Horticultural Sciences Department. The endowment is funded from donations made toward the State Wildflower License Plate program and provides graduate students the opportunity to continue conducting research on native wildflowers. So far, the Foundation has invested $300,000 in this endowment.

If Henry were here today, he would remind landscape architects that come after him to embrace the same principles that were reflected in his work throughout his lifetime.

“Conserve and protect Florida natural and scenic resources,” Caster said when asked what advice Henry would have for landscape architects today. “We are the profession with this ability and responsibility.”

In considering Henry’s programs, achievements and friendships, it is clear that he led a life that so many have been blessed to witness and take part in. Henry’s achievements revolutionized the way that Florida supports its native species and inspired others in his profession to prioritize the environment in their design, construction and planning decisions.