By: Mia Alfonsi

Too often, history is hidden from mainstream education or dialogue. This knowledge is undisclosed based on past social ideologies considering various aspects of history insignificant and warranting no further exploration. This past year, topics of systemic racism and inequities have been unearthed, but fortunately for diverse professionals who want to make an impact in their respective industries, so too have industry-defining contributions.

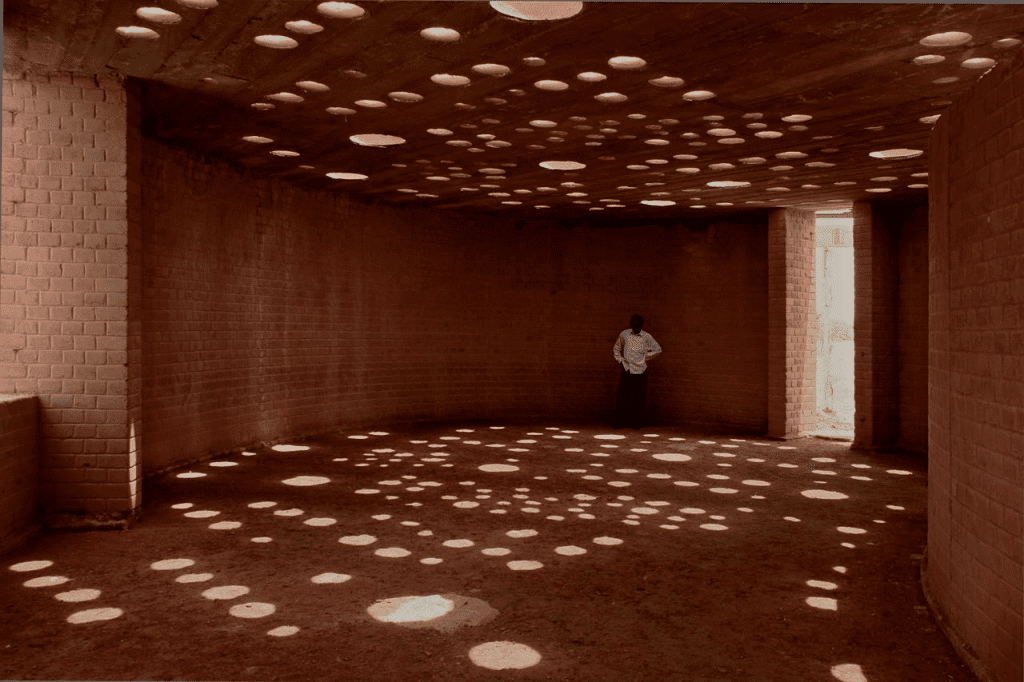

University of Florida College of Design, Construction and Planning Ph.D. student Amie Edwards seized the opportunity to shed light on African architecture, namely the Asante culture. While doing fieldwork for her master’s research in Ghana, Edwards was inspired to contribute to the marginalized literature that exists regarding African architecture.

Edwards’ discoveries in Ghana not only opened her eyes to the Asante and architectural prowess, but also to a new perception of Africa, which is typically not seen in the media, according to Edwards.

“The experience was enlightening,” Edwards said. “The vibrancy of the colors and the cultural elements was very telling about the way Ghanaians live and how they connect their spaces with the various elements of the landscape. That was my biggest takeaway.”

Edwards’ objective for her trip was to understand the Asante culture and the built environment. What she got was so much more; this experience moved her to pursue her Ph.D., which focuses on a 19th century Asante palace in Kumasi, Ghana, that was destroyed during the colonial period.

What is significant about her research is that, socially, when people think about African architecture, they immediately think of a type of shelter. However, there are other building typologies such as palaces that are not considered. From archives, Edwards has been working tirelessly to extract information on traditional building technologies and the social-cultural expression of the palace that is related to the Asante identity.

As a Black woman of African descent, Edwards’ exploration is both personal and educational; she is conducting research on African culture and contributing to a covert architecture topic. She believes that discussions of African architecture and similar rhetoric have not been discussed in mainstream education due to ideologies such as systemic racism in the architecture industry, which Edwards acknowledges still plagues today’s industry and the professionals in it.

Though architecture became a profession in the late 1800s, Jim Crow laws were an impediment to Black architects; they would get assigned limited projects because they were not part of the specific white framework. It was not until 1921 that the first Black architect, Paul Revere Williams, was recognized as a licensed architect, and in 1923, as a member of the American Institute of Architects.

Edwards believes her being a Black person has impacted her experience, wherein she is typically the “only” in the room on some occasions, a topic spoken about by many African Americans in the design industry.

“That isolation, not having any reference of leadership, not seeing someone in a faculty position or in the education material that is presented, is impactful and speaks volumes to our social issues,” Edwards said.

What empowers Edwards’ hope for the future in bridging inequities is her discovery that historical references to African Architecture, or unknown architectural contributions, exist, they just are not spoken about.

Edwards advises all students pursuing professions in these industries to discover something new.

“We are problem-solvers; we are creators,” Edwards said. “Do not be afraid to seek out something different that would advance the industry and bring forth innovation.”

Conversing with other professionals about the Black architectural experience while hosting DCP’s Black Alumni Event in March, Edwards realized she was not alone. There are professionals in the industry experiencing systemic racism and implicit biases that make for a feeling of exclusion. However, Edwards also commends the resilience on behalf of these professionals to contribute their talent despite obstacles.

This year especially, corporations and organizations have taken a stance or opened a dialogue related to systemic inequities and social justice. Edwards admires both UF and DCP’s pursuit in raising awareness for these issues. However, conversations are a starting point; real policy and action will make the change, Edwards warns.

“We have to get more inclusivity inside the textbooks and diverse faculty representation in the classrooms to reflect the society we live in,” Edwards said.

Her yearning to educate and highlight the unknown was not only the driving force behind her Ph.D., but also a clear catalyst to use her voice as a Black professional and guide the industry in productive and positive change.

“Once we get the education about it through recognition and understanding, we can move on and make inclusive policies for everyone,” Edwards said. “We are attaining knowledge for ourselves and discovering that which we are missing to make a change and impact the future.”