By: Chelsea Mistretta

“Madam Speaker, it is with great pleasure that I congratulate Cartaya and Associates Architects on their 40th anniversary in South Florida. Mario Cartaya and his firm Cartaya and Associates Architects have helped shape the look and architectural landscape of South Florida for our many visitors to enjoy.”

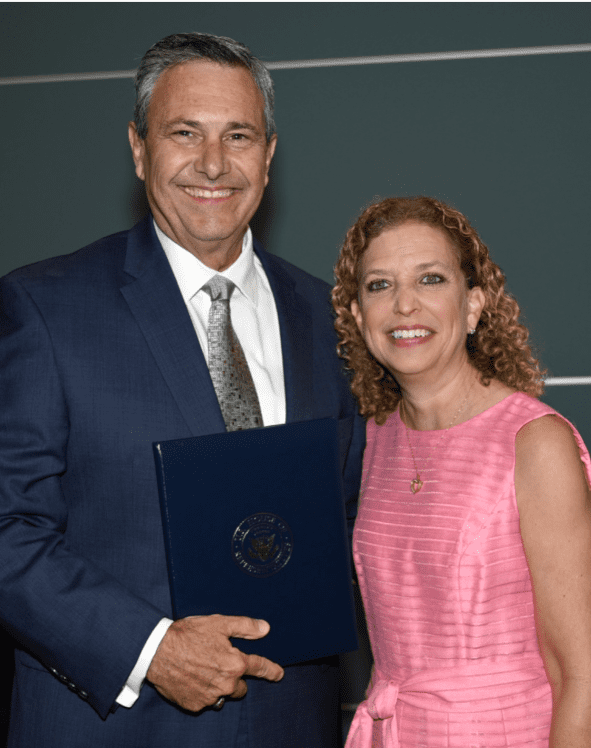

These are the words forever recorded in the Congressional Record in the Library of Congress. This is when a congressman reads for the record about citizens that have excelled in their districts or states. Very few readings are held. For his work around Broward County, Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz recognized two-time University of Florida graduate Mario Cartaya (BARCH ’74, MBC ’75), the founder and principal owner of Cartaya and Associates Architects.

Wasserman Schultz continued with:

“Mr. Cartaya is a visionary whose work can be seen throughout Broward County, from the Fort Lauderdale International Airport and several municipal centers to public libraries and performing arts centers, and even in our police headquarters and fire stations. Cartaya and Associates has also designed several additions and renovations for many hospitals and health care facilities in the area. Mario Cartaya has also dedicated himself to giving back to our community. He served as chairman of Broward College’s Board of Trustees, as a member of former Senator Bob Graham’s Air Force and Naval Academy Selection Committees and as a member of the Broward County Cultural Arts Council. He also served as an adjunct professor at Florida Atlantic University’s School of Architecture. His life has been dedicated to the pursuit of excellence in his professional career and the improvement of the community in which he lives. Mario Cartaya is a selfless, compassionate, and thoughtful citizen, one whom I am proud to call my friend. I applaud his work and wish him continued success.”

Cartaya did not expect this honor. He heard the news at a 40th anniversary party for his company. Congresswoman Wasserman Schultz called Cartaya to the stage with a “No party is complete before a surprise.”

She asked Cartaya to stand on the stage while she read what she said on the floor of the House of Representatives. After confirming to him that he will forever be in the Library of Congress, Cartaya began to cry.

“I did not cry for me; I cried for my father,” Cartaya said. “All that I could think was here is a man who sacrificed his life in Cuba and the family we left behind because he did not think my brother and I would be able to have the opportunities, liberty and freedom that we enjoy in America. My father abandoned everything: his life, the business he had created and being exiled. All I could think during her speech is what I wouldn’t give to have my dad alive and in that moment, to show him what he did and what he sacrificed is now celebrated today through my actions. That is why I cried.”

When Cartaya begins a project, he asks himself, “What does this building want to be?” For example, when he began designing the Pembroke Pines Charles Dodge Center, Cartaya kept asking himself this question. The answer he found was the building needed to be an example of democracy.

“I began thinking, okay what is democracy? Transparency. The transparency between those who govern and those who are governed,” Cartaya said, “Transparency is the fact that we the people can elect our representatives, who then meet with us, talk with us and take us into account while making the decisions that are going to affect us. This building has a 75-foot-high wall of glass. And that wall of glass is looking right at a plaza where the citizens converge, like a park. That glass is where the commissioner, the elected officials and even the mayor sit behind – the head of every department and all the leaders that are the problem solvers in the city. These stakeholders of governments sit behind that glass and look out at the park at their constituents. The constituents that go to this park can look through the glass and see their elected officials working for them.”

When asked the most difficult part of his career, Cartaya explained that it is inspiring and convincing others to share his vision to perfection and excellence.

When he began to work on the Broward County Courthouse, he did not think only of the judges and the courtrooms, but the people who were in family cases and those who were going through the most emotional experience.

“I realized very early on I needed to take care of the victims,” Cartaya explained. “I needed to take care of these poor people, especially in the family court, so that when they came here to meet a person who has done something emotionally unforgivable to them or someone in their family, that I can minimize their stress. Looking east to west and from the seventh floor on, which is where the courtrooms begin, you can see the ocean in Fort Lauderdale. That beautiful view belongs to the users – it belongs to these poor people, these poor families, not the judges.”

In his quest to give the victims in family court this view, Cartaya had to convince 97 judges to agree with him. People told him that it was not going to happen, that he was crazy. Cartaya convinced all 97 judges of his dream and made it happen.

Cartaya also finds it important to give back to the community. When asked why he found giving back important, he said, “I came to America when I had just turned nine. I was a little Cuban kid in a different land with a different language, different culture and different everything. This country took me in it when it didn’t have to, and it offered me an education. It offered me acceptance. It allowed me to go through a metamorphosis in which I became an American. How do you ever say thank you? Who do you say thank you to? I get involved and I give back.”

Cartaya graduated from UF Magna Cum Laude with a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1975 and a master’s in building construction in 1976. In 1979, he started his architectural firm. He has worked on more than 1,000 buildings in his career, which have earned many different awards. Cartaya is also very active in his community, serving on several different boards, such as the Broward County Arts and Design Committee and the Broward Chapter of the American Institute of Architects.